✈️ American Flyers Flight 280/D – Crash Snapshot

| Detail | Info |

|---|---|

| Date | Friday, April 22, 1966 |

| Time | Approximately 20:30 CST (Central Standard Time) |

| Aircraft | Lockheed L-188C Electra (Tail:N183H) |

| Operator | American Flyers Airline |

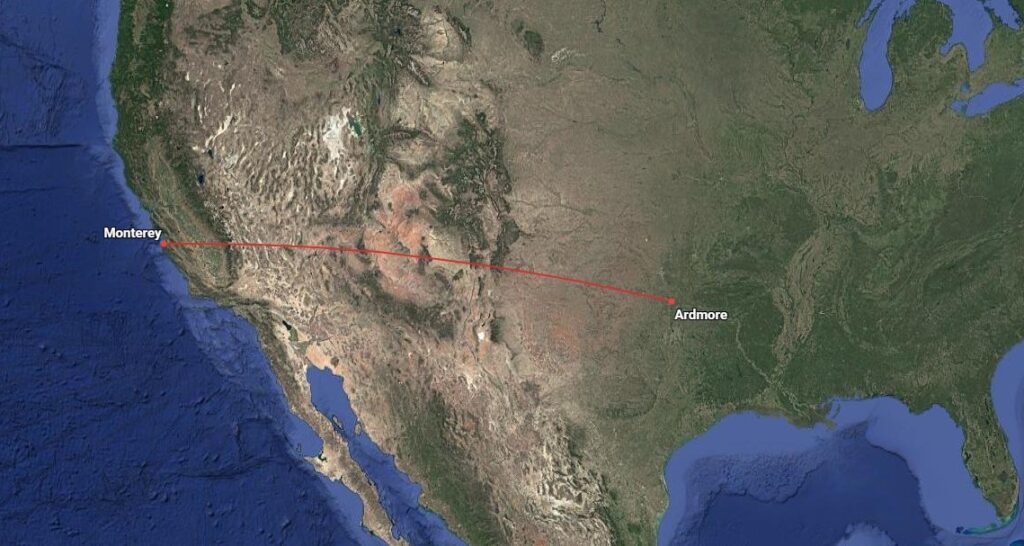

| From / To | Monterey, CA → Columbus, GA (via Ardmore, OK) |

| Crash Site | 2.4 km NE of Ardmore Airport, Oklahoma |

| Fatalities | 83 (of 98 aboard) |

| Impact | Hit hill during low-altitude approach |

| Damage | Aircraft destroyed by impact and fire |

| Cause | Incapacitation of the pilot-in-command due to coronary insufficiency during critical visual approach |

A Routine Charter Turned Horrific: The Calm Before the Storm

It was a quiet, ordinary Friday evening—April 22, 1966. But what began as a routine military charter flight would soon unravel into a night of fire, steel, and heartbreak in the rolling darkness of Oklahoma’s Arbuckle foothills. American Flyers Flight 280/D, a four-engine Lockheed L-188C Electra—tail number N183H, factory serial number 1136, born in 1961—took to the skies from Monterey Peninsula Airport (KMRY) at exactly 4:32 PM Pacific Time. Onboard were 98 souls: 93 passengers, many of them U.S. military personnel and their families en route to new assignments, and five crewmembers, veterans of the skies entrusted with delivering them safely to Columbus, Georgia.

Their aircraft was a marvel of postwar engineering. The Lockheed Electra, powered by four Allison 501-D13A turboprop engines, blended the speed and range of a jet with the reliability of a propeller aircraft. It was tough, resilient, and capable of operating from shorter runways than the new jets. The Electra had recently shaken off its troubled early reputation—its airframe once prone to destructive vibrations—but this one had logged a modest 4,019 flight hours. To all appearances, Flight 280/D was as safe as any charter could be.

But the Electra would never make it to Georgia. Nor would it return to Monterey. Just a few miles from its first stop in Ardmore, Oklahoma, the aircraft plunged into the ground, killing 83 of its 98 occupants in one of the deadliest non-scheduled air disasters in American history.

A Descent into Uncertainty: When Vision and Reality Diverge

As the Electra approached Ardmore Municipal Airport (KADM) under cover of night, the skies were not clear. Despite lacking thunderstorms or dramatic weather fronts, the approach was deceptively dangerous. Low clouds, haze, and insufficient visibility meant the crew would be flying by instruments—not by sight.

The ADF instrument approach they first attempted relied on an older navigation method involving Automatic Direction Finders (ADF), which used radio signals from a ground station to guide the aircraft to the runway. It required intense concentration, as ADF approaches lacked the vertical guidance provided by more modern systems like the ILS (Instrument Landing System). Pilots had to calculate descent angles and altitudes manually, guided by their instruments alone.

They failed that approach.

Instead of trying again, the crew chose to execute a visual circling approach to Runway 30. This maneuver is used when a plane approaches an airport from one direction but must land on a different runway due to wind or airport layout. The plane flies a curved path around the airport, descending gradually until aligned with the correct runway—a risky maneuver even in daylight, but one that becomes perilous when visibility is low or when clouds obscure terrain. Worse yet, circling approaches demand low, tight turns at altitudes often just a few hundred feet above the ground.

At 8:30 PM Central Time, just 2.4 kilometers (1.5 miles) northeast of Ardmore Airport, and at an altitude of 963 feet above sea level, the Electra struck a low wooded hill. The airport’s elevation was 762 feet, meaning the aircraft hit terrain that rose just 200 feet higher than the airfield itself—a fatal error of inches, not miles. The collision ripped the aircraft apart. A roaring fireball lit up the countryside. Local residents rushed toward the flames, but there was little they could do.

The Unseen Killer: A Captain’s Heart Fails in the Sky

The official investigation, conducted by the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB), was painstaking and grim. The wreckage revealed no major mechanical faults. The engines had been working. The flight instruments were functional. The aircraft had simply flown into terrain it should have avoided.

Then came the twist.

Autopsy results and cockpit analysis revealed a chilling truth: the captain—pilot-in-command—had suffered a heart attack. Medically termed “coronary insufficiency”, this condition occurs when the heart muscle doesn’t get enough blood flow, typically due to blocked arteries. In his case, it likely caused immediate incapacitation—loss of consciousness, motor function, and judgment—at the most critical moment of the flight.

Without the captain’s leadership, the remaining crew—possibly disoriented by the failed instrument approach, poorly briefed for a circling maneuver, or hesitant to take full command—lost control of the situation. In the haze and darkness, flying low and slow near the airport, the aircraft drifted into rising terrain. Controlled flight into terrain (CFIT)—a tragic term meaning the aircraft was flying perfectly fine, but under poor guidance, right into the ground.

Systemic Issues and Chain of Errors

While the captain’s heart attack was the initiating factor, the crash exposed deeper systemic issues:

- Crew Resource Management (CRM): This was a pre-CRM era. At the time, cockpit hierarchies were rigid, and junior officers were often hesitant to assert themselves, even in emergencies.

- Medical Oversight: The captain had a history of cardiac symptoms that may have been underreported or underestimated. The FAA’s medical certification system was not yet robust in detecting cardiovascular risk factors that could lead to sudden incapacitation.

- Airport Infrastructure: Ardmore’s non-precision approach lacked vertical guidance. The terrain to the southeast of the airport rose sharply—dangerous for circling maneuvers in poor visibility.

- Organizational Safety Culture: American Flyers, a charter airline, operated under Part 121 rules but with less scrutiny than larger carriers. Investigators questioned whether crew training and health monitoring met the necessary rigor for high-capacity flights.

The Fire, the Silence, and the Few Who Lived

The Electra was obliterated on impact, its fuselage consumed by flames fed by aviation fuel. Only 18 passengers survived the initial crash, dragged out by fellow travelers or ejected by the force of impact. Three of them later died from their injuries, bringing the death toll to 83 men, and women. The scene was apocalyptic: twisted aluminum, scorched uniforms, the acrid stench of burned hydraulic fluid, and the faint glow of embers in the Oklahoma night.

Local emergency crews were heroic in their efforts. Ardmore’s small-town fire department and local residents braved flames and falling debris to reach survivors. But the damage had been done in seconds. No distress call had been made. No time for a warning. Just impact, and silence.

Legacy in Flame: Lessons from Ardmore’s Darkest Night

The American Flyers 280/D tragedy didn’t lead to immediate regulatory overhaul, but it became a haunting case study in pilot health, approach protocol, and human factors in aviation. It underscored the limitations of visual approaches in marginal weather, the danger of pilot incapacitation during critical phases of flight, and the need for crew resource management—a concept not fully developed until years later, which trains all flight crew members to operate as a unit capable of assuming command in an emergency.

Today, the accident remains a shadowy, often-forgotten tragedy. But aviation professionals know its significance. The hill where Flight 280/D fell is just another rise in the landscape—but to those who remember, it stands 963 feet high in sorrow, regret, and eternal vigilance.