The Unseen Lifeline

In the vast, icy expanse of Canada’s Arctic, where roads vanish and winter reigns supreme for much of the year, a unique airline operates routes that global aviation giants wouldn’t dare. Canadian North isn’t just a carrier; it’s the indispensable artery of a region larger than many European nations, a lifeline connecting isolated communities across Nunavut, Nunavik (Northern Quebec), and the Northwest Territories to the rest of the world. Its story is not one of market dominance or cutthroat competition, but of strategic adaptation, profound resilience, and an unwavering commitment to a mission far beyond mere profit.

The Arctic’s Gauntlet: A Landscape Designed to Deter

The Climate’s Relentless Assault

For most major airlines, the Canadian North represents an operational nightmare. The challenges are not merely logistical; they are existential, forming a formidable barrier to entry that few commercial enterprises could overcome. The climate itself is a relentless adversary. Winter here is not just cold; it’s a -20°C to -30°C (-4°F to -22°F) assault that taxes every piece of machinery and human endurance, with winds that can cause frostbite in minutes. Prolonged periods of darkness plunge communities into months of twilight, while the infamous “flat light” conditions—where snow, sky, and horizon merge into a blinding whiteout—can disorient even the most seasoned pilot, severely impairing depth perception and judgment of distance.

This diffused lighting, which eliminates shadows and contrasts, is a known contributor to spatial disorientation, accounting for 10% of all commercial aviation accidents, and Controlled Flight into Terrain (CFIT), responsible for approximately 5% of aviation accidents. Studies specific to Arctic aviation operations indicate that over 30% of accidents in these regions are related to poor visibility, with flat light being a significant factor. Transport Canada’s own data reveals that visibility-related incidents, including those influenced by flat light, contribute to approximately 15% of aviation accidents in Canadian airspace, particularly in northern and mountainous regions. Sudden, severe blizzards, dense fog, and widespread ice make schedules a suggestion, not a guarantee, leading to frequent delays and cancellations, particularly during the transitional seasons of spring and fall.

Infrastructure: A Sparse and Challenging Network

Beyond the weather, the very ground beneath the aircraft presents its own set of obstacles. Forget gleaming terminals and endless asphalt. Many northern airports are little more than short, gravel strips, designed to minimize cost in remote locales. These unpaved surfaces are anathema to modern jet engines, which can ingest sand and gravel, leading to costly damage and compromising aircraft integrity.

Even a significant hub like Kuujjuaq Airport, while boasting an asphalt strip, also operates with a 5,000-foot gravel strip, a stark reminder of the mixed infrastructure. Beyond runways, essential services like sophisticated air traffic control equipment and procedures, robust aircraft rescue and firefighting (ARFF) capabilities, and extensive de-icing facilities are often limited or non-existent. Pilots describe these airports as “difficult to operate out of,” citing challenging and outdated infrastructure, and lamenting a perceived lack of government investment in airport upgrades.

The Economic Burden of Isolation

Then there is the sheer economic burden of isolation. Operating in the Arctic is astronomically expensive, impacting nearly every facet of airline operations. The cost of living in northern communities is significantly higher than in Southern Canada. Consequently, wages for airline personnel, including pilots, flight attendants, and ground staff, must be “much higher” to compensate, often supplemented by “northern living allowance[s]”.

Despite these incentives, attracting and retaining qualified staff remains a persistent challenge due to competition from other airlines in more accessible regions, leading to high turnover. The elevated cost of living extends to basic goods and services required for operations; for instance, a four-liter jug of juice in Iqaluit was reported at an astonishing $27.99, illustrating the extreme inflation that impacts everything from crew provisions to spare parts.

Aircraft utilization in the North is notably lower than in southern operations; Canadian North’s 737s are flown approximately one-third as much as those of major southern carriers like WestJet. This lower utilization means that the substantial fixed costs associated with expensive aircraft are spread over fewer flight hours, making them “expensive when you use them less”.

A Market of Necessity, Not Volume

Finally, there is the unique market itself: one of absolute necessity, not volume. The Canadian Far North, covering approximately 2.1 million square miles—40% of the country’s landmass—is home to a minuscule percentage of its population, living in small, isolated towns and villages. This sparse density translates to inherently low passenger demand, a death knell for airlines built on maximizing seat occupancy.

Crucially, there is “no road access to Nunavut from the rest of Canada and the introduction of roads will be highly unlikely in the foreseeable future”. This means air travel is not a luxury, but often the only viable means for both people and freight to move in and out of these communities, particularly during the long winter months when waterways are frozen.

Why the Giants Retreat: A Mismatch of Models

For major airlines, these challenges represent insurmountable barriers. Their business models are predicated on economies of scale: high passenger volumes, standardized fleets, efficient turnarounds, and predictable operations across well-developed infrastructure. Introducing specialized, rugged aircraft, absorbing frequent weather delays, or paying exorbitant operating costs for low-density routes simply doesn’t compute on a balance sheet geared towards shareholder returns.

Their modern jets, designed for paved runways and high-speed efficiency, are ill-suited for the gravel strips and extreme conditions of the North; their large, high-bypass turbofan engines are particularly vulnerable to foreign object damage (FOD) from loose debris, leading to costly repairs and potential safety hazards. The constant battle to attract and retain staff in remote, harsh environments, a struggle even for Canadian North, would be an even greater drain on resources for a major carrier without the same deep-rooted community ties.

Canadian North’s Masterclass in Arctic Adaptation

Canadian North’s enduring presence is a testament to a meticulously crafted strategy that embraces, rather than avoids, the Arctic’s unique demands. It’s a model of resilience built on specialization, adaptation, and a profound understanding of its unique operating environment.

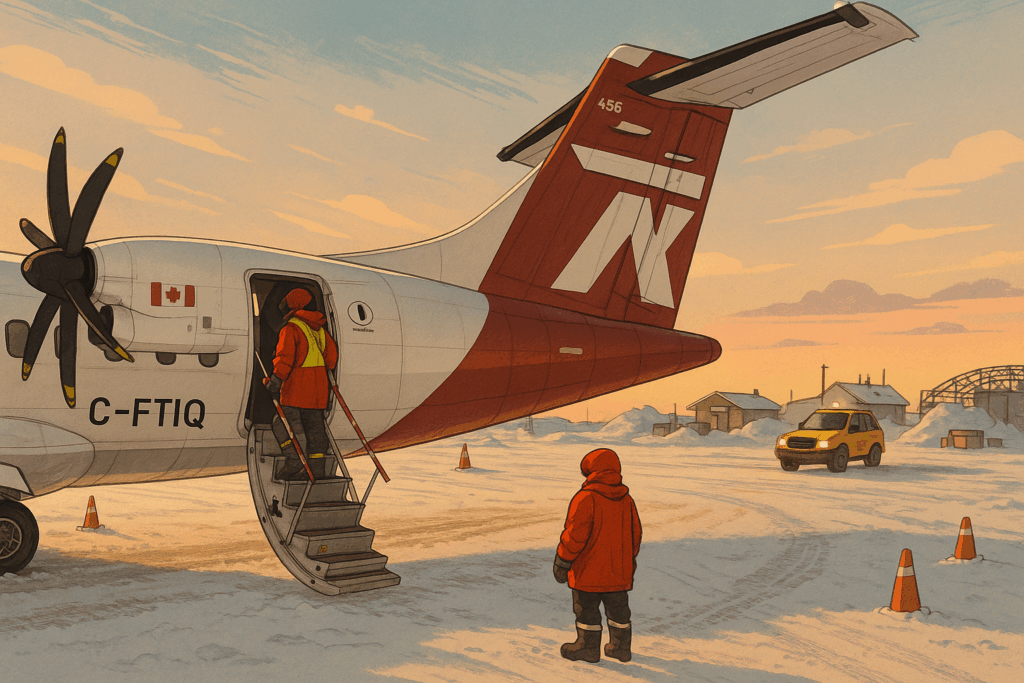

A Fleet Forged for the Frontier

At the heart of Canadian North’s operations is a diverse and purpose-built fleet, a blend of rugged workhorses and strategic connectors. Its ATR turboprops (ATR 42, ATR 72) are the true heroes of the remote North. These robust aircraft are explicitly designed and equipped for landing on gravel and ice strips, a non-negotiable capability given the prevalence of unpaved runways in many northern communities. Their versatility extends to “combi” configurations, allowing for swift reconfiguration to carry all passengers, all freight, or any combination in between, ensuring essential goods reach their destinations efficiently.

While its Boeing 737s (737-300, 737-400, 737-700) are not gravel-capable, they are strategically deployed on routes connecting southern hubs (like Edmonton, Montreal, Ottawa) to the larger northern airports (such as Iqaluit and Yellowknife), which boast asphalt runways. This intelligent fleet deployment maximizes both operational efficiency and safety across the Arctic’s varied infrastructure, creating a hub-and-spoke system meticulously adapted to the region’s constraints.

The “Essential Service” Business Model

Unlike typical airlines, Canadian North’s viability isn’t solely market-driven. A significant portion of its revenue, approximately two-thirds, is derived from providing essential passenger and cargo services to remote Arctic communities. This includes substantial government contracts for medical travel, work-related trips, and employee relocations, providing a stable, non-market-driven revenue stream. The demand for air cargo is particularly strong, as it represents the “quick and efficient way to transport goods to the isolated towns of the north,” creating a unique dual demand profile that standard passenger-focused airlines cannot efficiently address.

Government as Indispensable Partner

Recognizing air service as an “essential service” due to the lack of road access to Nunavut, the Canadian government plays a crucial role in Canadian North’s financial resilience. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the airline received a substantial $138 million in direct funding, notably through the Remote Air Services Program, ensuring service continuity when other carriers scaled back.

This partnership extends to a unique regulatory framework, including a profit cap (limiting net profit margins to 10% on its scheduled network, excluding major southern-linked routes like Edmonton-Yellowknife and Montreal-Kuujjuaq) and service obligations, such as guaranteeing at least one scheduled flight per week to all served communities and limiting average annual fare increases to 25%. This effectively transforms Canadian North into a regulated public utility, prioritizing community service over pure profit maximization—a model major airlines would never accept.

Cultivating Northern Talent and Unwavering Safety

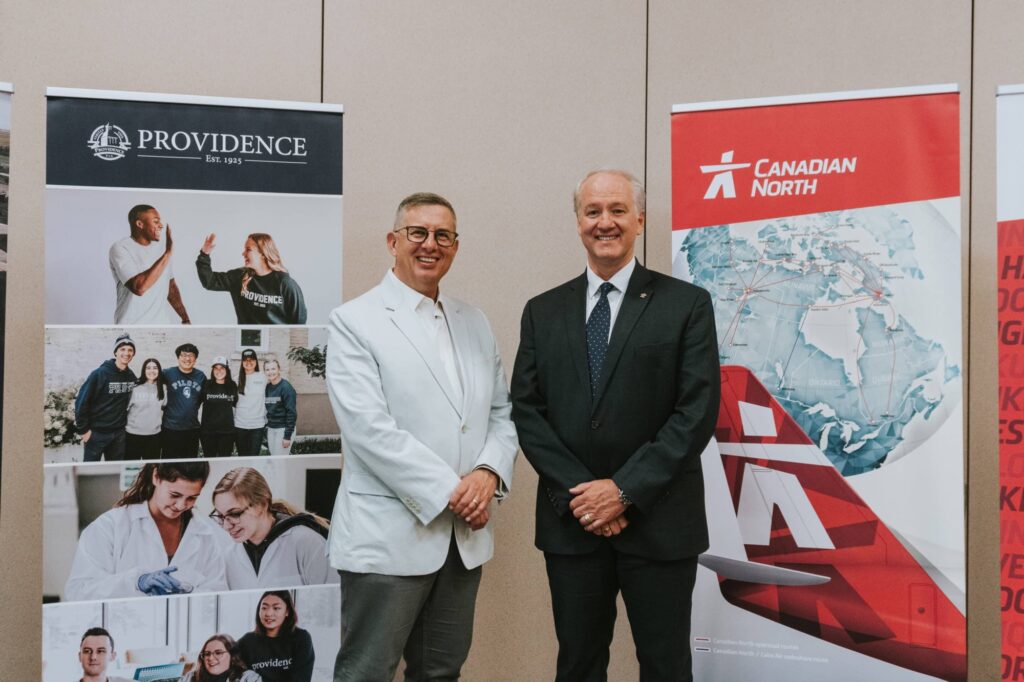

Operating in such extreme conditions demands exceptional human capital. The high cost of living and competition for talent are persistent challenges. To combat this and foster local economic self-reliance, Canadian North has partnered with Providence University College to create an Inuit pilot training program, offering employment to successful graduates.

This “from the North to serve the North” approach secures future talent and deepens community ties, representing a visionary, long-term solution to a critical labor shortage. Safety is paramount; pilots are highly proficient in instrument flying to navigate flat light, utilize advanced terrain awareness systems (EGPWS/TAWS), and adhere to a strict mantra: “If we can’t do it safely, then we can’t do it”.

This commitment often means flight cancellations due to adverse weather, a decision passengers understand and accept due to the airline’s unwavering focus on their well-being. Beyond flight operations, Canadian North implements extensive health and safety protocols, such as HEPA filtration systems on its Boeing jets and continuous cleaning and sanitizing of aircraft interiors, demonstrating a holistic commitment to passenger well-being.

Deep Community Integration: The Inuit Advantage

Finally, Canadian North’s 100% Inuit ownership is its defining characteristic, fostering a unique and profound relationship with the communities it serves. This intrinsic connection translates into a shared understanding of northern needs, cultural nuances, and challenges. The airline explicitly embraces its identity as “more than just a mode of transportation; we are a lifeline connecting families, we facilitate critical commerce and trade for the nation, and we support the unique needs of the North”.

This deep integration provides invaluable social capital, strengthening its operational mandate and community acceptance in a way no external major carrier could replicate. It aligns with broader initiatives for northern economic development, such as those supported by the Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency (CanNor), which works to build diversified and dynamic economies across the territories.

The Indispensable Link

In a world increasingly connected, Canadian North stands as a powerful anomaly. Its success is not measured by the number of passengers on a transatlantic flight or the competitive fares on a bustling southern corridor. Instead, it’s measured by the fresh produce delivered to a remote village, the medical patient reaching life-saving care, and the families reunited across vast, frozen landscapes.

Canadian North’s operational model is a masterclass in strategic differentiation. It is a testament to how deep specialization, unwavering adaptability, and a profound commitment to a unique mission can not only survive but thrive in an environment that systematically deters the world’s largest aviation players. For Canada’s North, Canadian North isn’t just an airline; it is, quite literally, the difference between isolation and connection, between scarcity and sustenance. It is the indispensable link that keeps the Arctic alive.